Articles

Why Horror Is the New Mythology

by E. D. Grey

There’s an ancient Greek tale about a man who wandered into a sacred grove and saw Artemis bathing in a waterfall. As punishment, she turned him into a beast.

In ancient Greece, the city was everything—order, identity, safety. Beyond its walls lay the wilds: untamed, unmapped, and lawless. To venture out was to risk death by beast, exposure, or enemy capture. But the greatest fear was treachery. A Theban might flee to Athens and betray his people. So how did the city keep its citizens close?

Simple. It told stories.

Stories of gods and monsters lurking in the trees, waiting for the curious and the disobedient. Myth became a mechanism of control—elegant, symbolic, and terrifying.

Today, those myths have lost their original context. Artemis in the wild no longer warns us of civic betrayal. But the abstraction remains. The beauty of myth lies in its ability to transcend its origin. Zoom out, and the lessons of the Olympians—or the Bible—still echo. They speak of sacrifice, temptation, transformation. But to hear them now, you need an archaeologist, a historian, and a priest. Most of us are left with fragments.

And yet, we still crave meaning.

We are no longer satisfied with tales of ultimate sacrifice or heroic conquest. Technology has made such feats feel distant, unnecessary. What matters now is emotional and psychological. Our minds are wired to seek the highest possible good—love, safety, connection. We still need stories that teach us how to live, how to suffer, how to survive. But we need them in a language we understand.

This is where horror comes in.

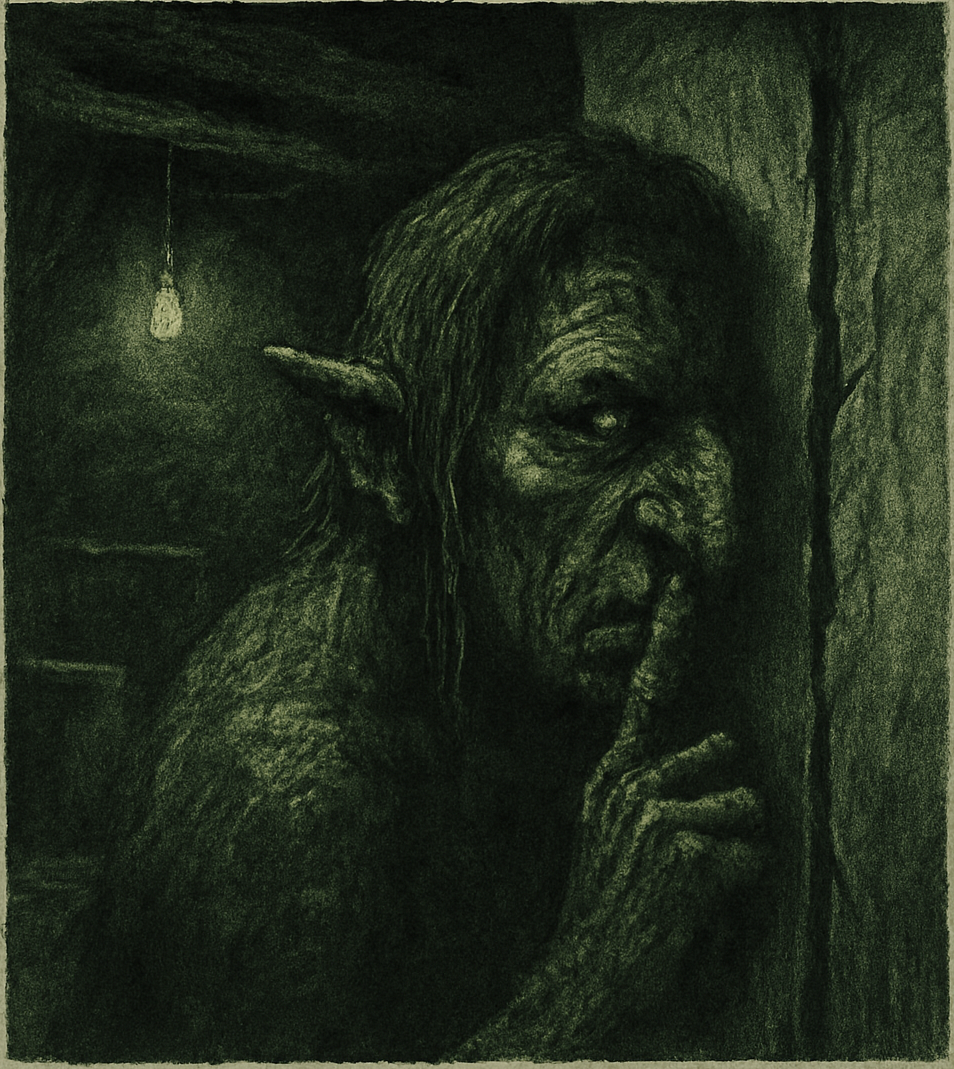

Contemporary horror is the landscape where myth and theology now reside. It is the new sacred grove—accessible, immediate, and emotionally real. The monsters of ancient stories still walk among us. Their names may change. Their forms may shift. But their warnings remain.

Now the Black Shuck, the Troll, and the Tikbalang live in your basement.

They whisper through the walls.

They remind you what it means to be mortal.

Folklore Across Borders: Writing Toward Understanding

by E. D. Grey

We only resort to conflict when understanding fails.

Since I began writing, my objective has remained the same: to explore humanity and expose readers to cultures and folklore they might never otherwise encounter. I have a personal connection to both British and Filipino culture, which is why I chose the folklore of these two very different civilizations as the foundation for my first two manuscripts.

Symbolism and Cinematic Imagery in Storytelling

by E. D. Grey

Symbolism is quite possibly the most important tool in a storyteller’s kit. With a single well-placed object or configuration, we can pack a sublime amount of detail into a paragraph—without weighing it down. Objects revealed in the right order, or placed in relationship to one another, can tell a story by themselves.

Humans are visual beings. We learn by observation. We hunt by sight. Even the word sin—to miss the mark—comes from our ability to aim. One of the greatest metaphors in our world is born from a sight-specific skill.

This is why I believe imagination is so powerful. It helps us find a path forward. It helps us arrange our memories. But it’s more than that. Our nightmares terrify us precisely because they are personal. What frightens me may not frighten you. So why would I describe in exhaustive detail what I fear, when I can hint at it and let your imagination do the heavy lifting?

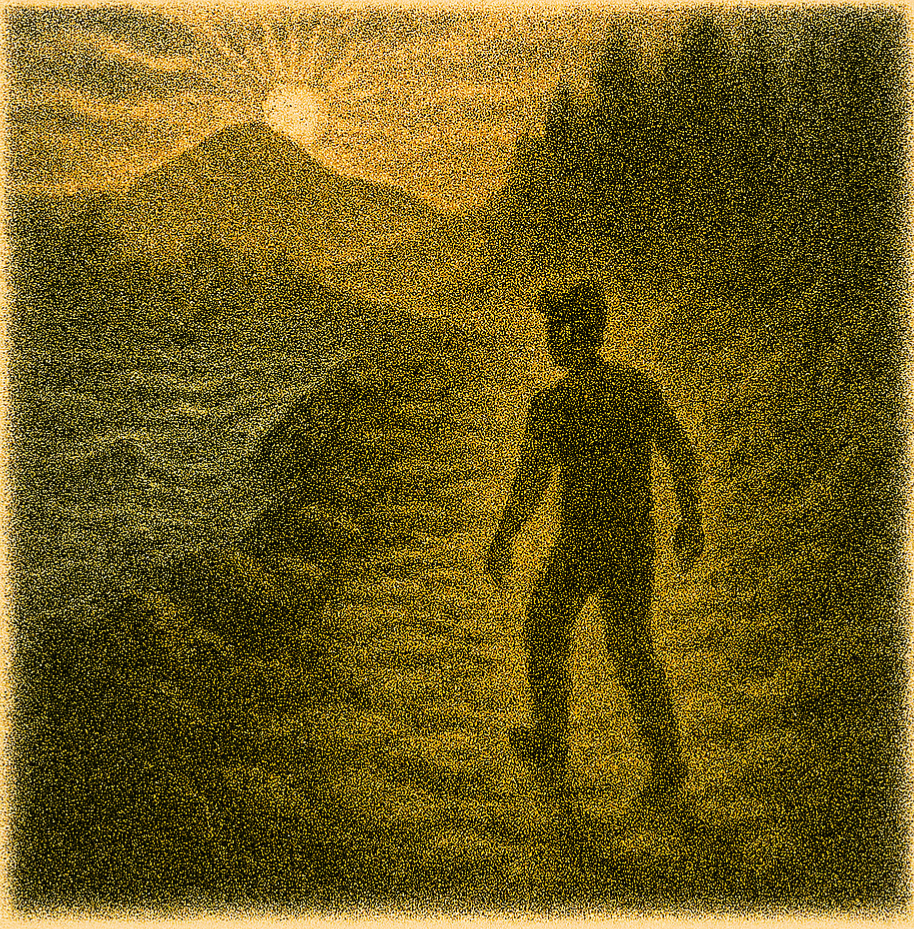

This is where so many horror films falter—they reveal the monster too soon. The monster should remain unseen until absolutely necessary. Until then, it is a shadow. A half-glimpsed presence. The same principle applies to beauty, to grief, to awe. There is a commonality that moves us, and that is what symbolism must tap into.

Symbolism isn’t restricted to objects. Image composition is a powerful tool. A boy crawling through a mud-slicked tunnel into an underworld cave to face a flaming monster with nothing but his faith and heart—that image reminds us of our own inner demons. The symbolism lives in the narrative. And the narrative comes to life in our imagination.

Embrace the power of the audience’s imagination, and your story will echo across time and space.

What struck me most when learning about the Philippines was how present the spirits are in everyday life. The people of those lands know the beings that haunt their forests. They speak of them, fear them, respect them. In contrast, in the U.K., I’ve rarely met anyone who’s heard of the Black Shuck, or Brownies, or the witches and spirits that once shaped our moral imagination. These figures still exist—in quiet corners of academia—but their presence is largely hidden. Unlike in the Philippines, British folklore has been buried beneath centuries of upheaval.

That’s why I chose to set Something in the Soil in the U.S.A. With its large Filipino population, America may benefit more than anywhere else from understanding Filipino culture. Through story, we can find common ground—shared fears, shared hopes—and build empathy where ignorance might otherwise grow.

In the U.K., our sense of cultural identity has been fractured. A turbulent history of conquest and rapid change left many unable to keep up. Languages shifted, trades evolved, and the stories that once defined us were forgotten. But Britishness isn’t just the epic clash of kings—it’s also the tales we told our children to keep them from wandering too far into the woods.

I don’t write for children, though. I write for adults—because we need grown-ups to understand who we are as peoples, so they can more intuitively teach the next generation.

That makes it all the more important to respect the source culture. Folklore belongs to living communities, whether actively remembered or quietly endured. I’m in the business of sharing love for folklore—not debasing it.

Folklore carries moral imagination, history, and social memory. When writers transplant a spirit or tale into a new landscape, they aren’t just moving an image—they’re moving meaning. Done well, this work builds empathy, reveals shared human concerns, and helps readers see their own world anew.

These stories are just the tip of the iceberg. There’s much more work to do. This is the ring I’ve chosen to step into, and I’ll keep going as long as I can.

Introducing folklore across cultures is an act of translation—and translation is an act of care. When we bring a spirit into a new landscape, we also bring responsibility: to research, to listen, and to honour the tale’s original function. Do that, and folklore becomes more than ornament—it becomes a bridge. It can teach readers how different peoples understand fear, love, and loss. And it can help us all see how small our moral worlds truly are.

Why I Write for Discomfort

By E. D. Grey

Comfort, to me, is not a starting point—it’s an end goal. Life, by its nature, demands that we experience the full spectrum of being: joy and grief, safety and danger, love and loneliness. And if we’re lucky, we face the worst of it while we’re still young—when our spirits are flexible, when we’re better equipped to confront the harshness of reality.

Comfy stories are nice. They shelter us. They offer warmth and ease. But they rarely teach us how to earn the life we want. They skip the struggle. They bypass the monsters. And in doing so, they leave us unprepared.

True comfort is earned. It’s the reward for swimming dark waters, walking hard roads, and battling the monsters in our hearts. It’s not something we’re given—it’s something we fight for. And giving into comfort too early, too easily, is just another way of giving into the monsters.

Except, perhaps, when we’re old. When our fighting days are behind us. Then, comfort becomes something else entirely—a well-deserved rest. But until then, I write discomfort. I write tension. I write stories that hurt before they heal.

Healing only happens when we’re hurt. It sounds obvious, doesn’t it? But what if we deny the hurt? What if we pretend it doesn’t exist? The real suffering often comes not from the wound itself, but from the quiet acceptance of our own inadequacies—our mistakes, our naivety, our fear.

In horror and thriller fiction, the action is often seen as the focal point. The chase, the scream, the blood. I feel that pull when I write—the temptation to let the monster loose. But the real magic lies in the build-up. That’s where the stakes rise. That’s where the meaning behind the conflict becomes visceral.

When I was a student of theatre performance, we used to do this exercise: we’d have an intention, a story to tell, an objective to fulfil—but instead, we’d talk about the weather. The action never happened. But the tension built. And suddenly, the smallest gesture, the quietest pause, carried weight. That’s how I learned that humanity exists between the events. In the little things. The quiet, uncomfortable silences.

Horror works the same way. The monster you never see is far scarier than the four-headed hydra with poison dripping from its teeth. Give the audience room to imagine, and they’ll conjure far more terrifying images than I ever could. Because fear lives in mystery. In suggestion. In the space between.

Characters have to be flawed. Otherwise, there’s nothing for them to learn. No necessity for redemption. No reason to change. Unless we’re talking about a fantasy epic—and even then, the most compelling heroes are the ones who stumble.

Flawless characters are boring. Confusion is human. It allows for mistakes, for growth, for grace. The ones who know exactly what they think or what they’re doing are often liars, fools, or destined to cause utter destruction. Because certainty is rarely honest. And clarity, when it comes, is hard-won.

Discomfort is the crucible of transformation. Characters get out of bed in the morning because something needs to be done—whether it’s work, household chores, or something deeper they don’t yet understand. And isn’t that life? Who really knows what they’re doing? No one. We muddle through. We flounder. We make mistakes. And if we’re lucky, we learn something along the way.

No one knows the truth. Not really. And maybe we never will. But we keep going. We keep struggling forward. Because the act of trying—of facing discomfort, of walking the hard road—is what makes us human.

My hope is that readers of my stories will find an emotional and psychological realism seldom found in storybooks. Experiences that reflect their own, or serve as warnings. I don’t have all the answers. I never will.

But if you sit with me—on the cold floor, in the dark silence—and embrace the void, you might find your own.

A love letter to dogs.

By E. D. Grey

There’s an ancient folklore from East Anglia about a dark omen known as the Black Shuck. A spectral hound with eyes like burning coals, said to appear before tragedy strikes—a herald of doom. The name itself, Shuck or Scucca, is thought to be the root of our modern word shock—a term that describes a sudden spike in fear, an involuntary jolt of the nervous system. The Shuck doesn’t just arrive. It interrupts.

Traditionally, the Black Shuck is depicted as a monstrous dog, huge and silent, stalking roads and graveyards, churchyards and coastlines. Its presence is a warning. Its gaze, a curse. But I’ve always wondered: where did this belief come from? What ancient fear gave rise to the myth?

I suspect it dates back to a time when wolves still roamed Britain. For a person walking alone in the dark, or a family huddled around a fire, the threat of a wolf was real and terrifying. A creature that could vanish into the trees, then reappear with teeth bared. The Black Shuck, then, may have served a practical purpose—a story to keep children close, to explain the unexplainable, to give shape to the shadows.

But here’s the paradox: wolves are ambush predators. Like big cats, they rely on stealth. They don’t announce themselves. They don’t walk into a clearing and declare a prophecy of doom. That’s not how predators behave.

So, what if the Shuck isn’t a predator?

What if it’s not a wolf at all?

What if it’s a dog?

The dogs in our communities serve a necessary purpose. They are our guardians, our comfort, our guides. And they do this not for pay, not for prestige, not for career advancement. They do it because they want to. It is a pure act of love—unconditional, instinctive, and often unacknowledged.

In fiction, especially horror, I’ve often found that dogs don’t get the respect they deserve. They’re loyal, intelligent, emotionally attuned—and yet far too often, they’re discarded. Killed off early. Treated as expendable. I find myself saying to my wife, almost ritualistically, when we watch horror films: “Of course the dog will die. That’s why he’s here.”

Because dogs are so loyal, so reliable, horror can’t truly exist while they’re around. Their presence disrupts dread. Their protection interrupts fear. So the genre removes them. Not because they’re weak—but because they’re too strong.

And that’s why I believe the Black Shuck, also known simply as the Black Dog, cannot be a predator. It doesn’t behave like one. It doesn’t stalk or ambush. It appears. It warns. It watches. It cannot stop people from doing foolish things—but it tries. And when tragedy follows, it’s not because the Shuck caused it. It’s because we didn’t listen.

The Black Shuck is not a beast. It is a guardian. A witness. A creature of deep instinct and deeper compassion. And in The Black Terror, I wanted to reclaim that truth. To write a horror story where the dog is not the victim, not the monster, but the guardian, the companion. The one who knows what we need even when we do not.

I grew up in a busy, noisy little working-class house. The only real stability I had came from my dogs. The most memorable of them were Leo, a Shar Pei, and Millie, a Labrador.

Leo was a nutcase when he was energised—frantic and chaotic, especially on long trips. But he could also be gentle, kind, and fiercely protective. Nothing made me feel safe like that dog. Then there was Millie. Playful, tender, attentive. More than anything or anyone else, she was my best friend. She taught me what love is.

I’ve tried to reflect both of them in The Black Terror. Their loyalty, their complexity, their quiet heroism. And I’ve contrasted them with a villain who reflects the trouble in my past—the chaos, the control, the fear. Because this story isn’t just horror. It’s healing. It’s reclamation.

This story is for Leo and Millie. For the dogs who watched over us when no one else did. For the ones who didn’t need words to understand us. For the ones who stayed.

It’s for every dog that has loved and protected us—not because they had to, but because they chose to. Fiercely. Unconditionally. And without fail.

Author’s Note

This piece is deeply personal. The Black Terror began as a love letter to the dogs who protected me when I had no one else. Leo and Millie weren’t just pets—they were my guardians, my teachers, my friends. Horror gave me the language to explore trauma, loyalty, and redemption. This story is for them, and for every dog who’s ever stood between a person and the dark.

If you’ve ever been saved by a dog, you already understand.